I would appreciate suggestions on how to handle languages where words can have many different forms. If I highlight a word only this particular form is recognized in texts. It is fine for languages like English or Chinese, but not so good for Finnish or Spanish. How to use Readlang effectively in this case?

A couple of thoughts… If I believe the word is probably in a specific form, I will try to understand (like ask the AI) what kind of form that is. Possibly I can add something about that to the word’s definition, but also hopefully I will start to recognize that form as a pattern across other words.

I’m inclined to spend more time on the same text, and reviewing the vocabulary from that text, so that in the future I might have better ability to remember that I have seen some form of a word. This is basically trying to compensate for readlang not being able to remind me that I’ve seen a word before, just in a different form. (readlang’s reviews are based on spaced repetition, but I like to spend some time trying to cram a text’s entire new vocab list. If nothing else, it makes that text more accessible for reading or listening.)

But, I’m not sure if it (i.e. additional review of texts in such languages) is critical. Suppose you at one point encounter the (Spanish) word “hablo” and then in another text you later find “hablas.” It would be great if readlang could call out “hablas” for you as something that might be familiar, because you could stop and ask yourself if you can guess it. But since it doesn’t do that, the alternative is that you click “hablas,” get the meaning, and hopefully it could ring a bell that in the past you’ve seen a similar word. It’s less effective that way, but it’s not hopeless.

When I drill/review vocabulary that takes different forms, even when I “learn” that XYZ means some English word I know, I recognize that I probably do not know how to use XYZ in a sentence (unless I’m confident what form it’s in and what that means). Maybe that’s obvious. But additionally, I don’t think it’s a good use of energy, anyway, to worry about whether you can form proper L2 sentences while drilling vocabulary on readlang.

Interested in other takes.

I’ve described my approach here:

The “note” field could also be used for this:

Thanks so much! Both of your answers gave me a lot to think about!

@M_C, I totally get what you’re saying about seeing a form like hablo and later running into hablas without Readlang showing the connection. That’s exactly what’s been frustrating with Finnish. For example, I save taloa but then don’t realize later that talossa or talon are the same base word unless I stop and check. I’ve also started using Ask AI feature to figure out what form something is, and I like your idea of reviewing the full vocab list from a text before moving on. It makes sense that getting deeper familiarity with a smaller chunk of text helps build up that mental connection between forms.

@Anna_Vernerova, your note about using the synonym or note fields creatively is brilliant, especially tagging things like GEN for genitive. I never thought about doing that, but it opens up a lot of possibilities for tracking grammar patterns. I’ll try experimenting with that kind of tagging system.

For now, I’m thinking of starting a similar convention for myself, something like always adding the base form (like mennä) in the synonym field and the grammatical function (like “ILL” for illative) in the notes. That way I can search and sort better later.

Still open to more suggestions, especially if anyone has a semi-automated way to detect base forms or link conjugations together inside Readlang.

I add all forms and ask AI to give me examples of usage in all forms.

So what would you prefer to happen instead, and what would you accomplish if it did?

Ideally, all forms of that word should be found and highlighted in texts. But realistically it is not possible in Readlang. Readlang currently treats each word form as a separate entity, which creates some challenges.

Current Limitations

Entry Proliferation

Each word form generates its own entry and flashcard. While manageable in English, this becomes problematic for morphologically rich languages like Finnish, where a single word can have hundreds of forms, leading to an overwhelming number of entries in the word list.

Dictionary Integration Issues

Dictionaries typically work with base forms only. When encountering inflected or conjugated forms, additional searches must be performed that may fail to return accurate results.

Posible Improvements

Manual Form Addition

Allow users to manually add word forms to existing entries. Since synonym fields are already available, I try to use them for this purpose.

Enhanced Text Highlighting

Enable highlighting of synonyms and manually added forms within texts, not just the primary word entry.

Entry Consolidation

Provide functionality to merge multiple related entries from the word list into a single consolidated entry, reducing clutter and improving organization.

Not too sure how useful it might be. However, if one could tag words like you can tag notes in Apple Notes or files and folders in MacOS, perhaps a tagging system could prove straightforward and useful. So: add a tag to any word. When viewing a tagged word, provide some indication of tag(s) that exist and when you click on that tag, it reveals or takes you to the list of all words with that tag.

It would be up the the user to choose the tag, which could be the “reference” form such as the nominative singular of a noun or anything of the user’s choosing.

Back to your original question: I’ve been learning Russian for over three years now. Russian nouns have a minimum of 12 forms. Russian verbs conjugate like many languages based on 1st, 2nd person, etc. So in a system like Readlang of Lingq you do end up with a lot of duplication never really connecting those various forms.

For me, when I finally understood the fundamentals of the Russian grammar - the rules dictating spelling changes plus declensions and conjugations directly tied to those spelling changes, the multiple forms became a virtual non-issue for me. Дом, дома, дому etc. - it’s all “home” to me. At that point, the specific forms no longer mattered. The app did not need to handle it for me.

That certainly was a pain point for some time in the beginning. Not saying it wasn’t, but it no longer is.

Sure, a tagging system would give users the flexibility to group related word forms however makes sense to them. It would be much more user-controlled, and could work across different languages with varying complexity. It would definitely help manage large word lists better than the current separate-entry system.

That’s exactly the issue - while you’ve internalized that дом, дома, дому are all variations of the same concept, Readlang still treats them as completely separate entities. Even though your brain has made that connection, you can’t consolidate your learning materials to reflect that understanding.

The real value of consolidated entries becomes clear when you want to add context - usage notes, mnemonics, or examples of interesting constructions. Right now, if you encounter one form and want to note something about the same word in another form, that note gets buried under just one form instead of being accessible across all related forms.

And while 12 Russian noun forms might feel like a lot, Finnish takes this to an extreme with potentially hundreds of forms per noun through case combinations, possessive suffixes, and clitics. A Finnish learner could easily end up with 100+ separate entries for what’s conceptually a single word. At that scale, the current system becomes completely unwieldy - you’d need some form of consolidation just to navigate your word list effectively.

Good points. I can’t speak to Finish, but I can tell you a tale of two teachers. True personal story.

I had a teacher on iTalki. He had an amazing grasp of Russian. He filled out a declension table for me of Russian nouns. 12 cases, three genders. So far so good, but you must account for spelling variations per the spelling rules and some exceptions. He didn’t bother to consolidate forms so his collection of suffixes totaled about 64 endings. And that does not account for adjective declensions. I was rattled by the complexity.

Then I went to university to learn from an old school soon to retire professor. He taught me the rules, I could then make my own simplified chart with a minimum amount of noted endings. Finally sanity had come to Russian learning.

My point is: better, if possible, to learn how to transform the root word - the form you’re going to find in a dictionary - than try to memorize all possible forms.

Absolutely agree - learning the transformation rules is far more efficient than brute force memorization. Your university professor had the right approach.

Finnish actually illustrates this perfectly. While Finnish can generate hundreds of forms per word, the agglutinative nature makes them more transparent than Russian forms. Take “talo” (house): talossa (in the house), talossani (in my house), talossanikin (even in my house). Each suffix has a clear, predictable function, so once you understand the patterns, you can parse these complex forms systematically.

Russian, being more fusional, can be trickier - “дому” doesn’t obviously indicate “dative singular of дом” to a beginner the way “talossani” clearly shows its component parts to someone who knows Finnish grammar. Or consider дома. It can be either genitive singular or nominative/accusative plural of дом, depending on where the stress falls: до́ма vs. дома́.

But here’s where Readlang’s current system works against efficient learning: even when you’ve grasped that “talossa,” “talossani,” “talossanikin” are all variations of “talo”, you’re still stuck with separate entries for each form. You can’t consolidate your notes about how “talo” behaves in different contexts, or track your overall progress with this word.

Being able to group these forms under a single entry would actually reinforce the transformation approach - you’d see the root word as the anchor, with all its variations organized beneath it, making the grammar patterns more visible rather than scattered across dozens of separate flashcards.

I personally find there’s two kinds of Finnish forms:

If a word is regular, then I only ever enter one or two of all the possible forms into ReadLang. When I encounter the other forms later on, I simply recognize them - no need to click on them.

If a word is irregular, or even if it is regular but I encounter a form that I cannot create reliably, then it is a good thing that each form gets its own ReadLang entry (e.g. siitä vs. sitä, partitive plural forms, past tense forms etc).

If I encounter an interesting phrase, I often highlight all of it, creating a separate flashcard for the whole combination. That’s because while I may know each of the individual words well enough, I may find it much harder to combine those words in just that way, and I want the revision interval for the combination be short.

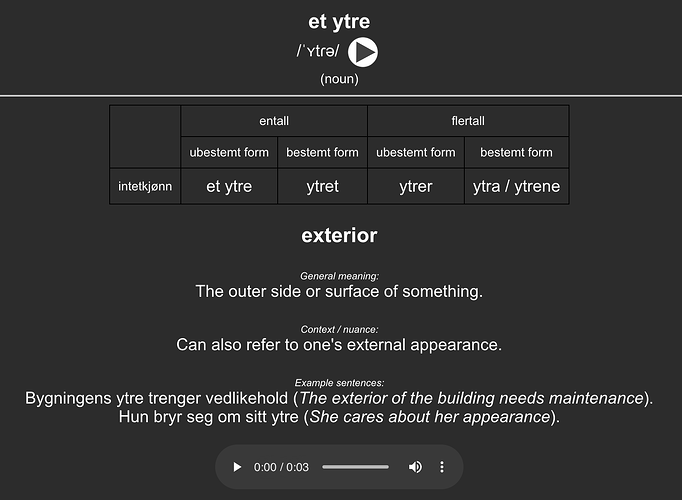

Readlang’s spaced repetition system is quite frankly terrible for multiple reasons. What I do is ignore it completely and just export the words into a CSV file, which I later feed into ChatGPT instructing it to generate flashcards for Anki. The result can be quite impressive and you can customize it to your specific needs. Here is an example of what I consider a useful flashcard backside. I imagine this approach would be particularly beneficial to languages with many forms.